Don’t Vote for This Man: How Election Messaging Escalated

- friendsofkenlake

- Dec 7, 2025

- 5 min read

Updated: Jan 9

A communication analysis of Gowrylow’s “Not So Fun / Don’t Vote for This Man” flyer

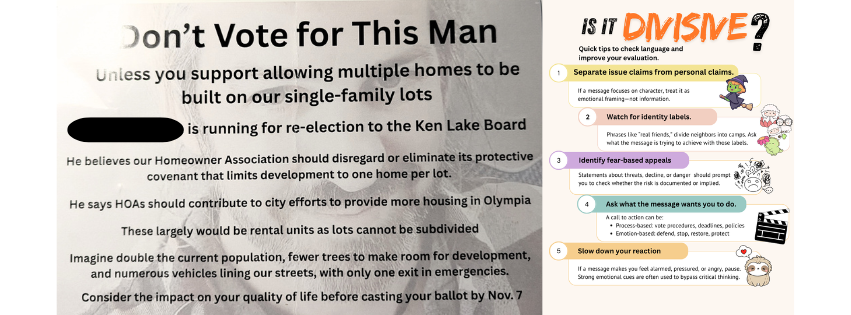

As the first flyers of the 2025 election hit doorsteps, neighbors received a set of campaign materials that included the “REAL Friends of Ken Lake” flyer and, alongside it, a separate two-sided flyer focused entirely on one candidate.

Disagreement is expected in any election, however it is unusual for HOA materials to focus so extensively on a single neighbor’s character rather than on governance issues.

While the first flyer used contrast-based political framing, this second flyer escalated that tone— centered not on competing ideas or visions, but on a series of personal allegations and warnings. Because this flyer significantly shifted the emotional climate of the election, this article looks at the communication patterns in this specific document.

A separate article will review the factual accuracy of the statements based on documents and meeting records.

In all materials, names of individuals targeted will be redacted. We would ask readers to imagine their own names in that place instead.

Tone and Format: A Move from Contrast to Personal Accusation

Unlike issue-focused campaign materials, this flyer concentrates entirely on one neighbor. The text employs:

direct personal accusations

legalistic terms ("punitive lawsuits," "violates ethics rules")

commands ("Don’t vote for this man")

moral framing

statements presented as fact but without citations

This is a significant escalation from comparing visions to portraying a specific neighbor as personally dangerous.

The “Bullet List” Effect: Stacking Claims Without Sources

One side of the flyer presents a long sequence of “Not so fun ‘facts’.” This communication pattern—claim stacking—creates the appearance of confirmed wrongdoing simply through volume.

Characteristics:

No citations

No supporting documentation

No dates, references, or links

No ability for the reader to verify context or accuracy

Stacking allegations side-by-side makes them feel official, even when none provide evidence.

Housing Fear Narratives and Speculative Harm

The reverse side of the flyer focuses on housing density, renters, traffic volume, and emergency access. The language relies on speculative scenarios written as near-certainties:

“Imagine double the current population…”

“Fewer trees to make room for development…”

“Numerous vehicles lining our streets…”

“Only one exit in emergencies…”

This rhetorical technique—fear projection—invites the reader to imagine the most extreme version of a hypothetical change and treat it as a guaranteed outcome.

The flyer does not provide:

any proposed policy,

any motion to alter covenants,

any documented plan to increase density,

or any connection to actual board actions.

Delegitimization of a Candidate’s Participation

Throughout both sides, the flyer repeatedly asserts that the named candidate:

threatens compliance,

manipulates others,

causes resignations,

endangers the community, or

seeks harmful changes.

These descriptions frame the candidate not as someone with different ideas, but as someone who is inherently unsafe for the neighborhood.

This strategy shifts the election conversation from:

“Which policies make sense?” to “Which neighbors should be distrusted?”

Such framing can discourage participation, reduce constructive dialogue, and heighten personal anxiety.

A Note on Who Gets Targeted — and Who Doesn’t

It is important to recognize that not being targeted by this kind of messaging does not mean someone is “doing things more correctly.” It only means their communication style or role in the conflict did not make them the focus of a fear-based narrative.

When a single person is publicly framed as the source of a community’s problems, it often reflects:

Targeting is not evidence of misconduct. It is evidence of how someone else interpreted the situation — often under stress, with partial information, and without examining the impact of their own behavior.

Understanding this distinction helps us avoid confusing “not being named” with “being more appropriate,” and helps us read the flyer as a narrative choice, not a factual conclusion. |

Use of Implied Authority

The flyer is signed: “Lakemoor Board member Mike Gowrylow.”

From a communication analysis standpoint, this signature:

lends the flyer perceived institutional weight,

signals insider status,

implies access to privileged information, and

may lead readers to assume the allegations reflect official board knowledge.

The flyer does not clarify that it represents individual opinion, not the board.

Impact on the Election Environment

Because we do not assume intent, this section focuses on observable impact, not motive.

This flyer introduced:

A shift from policy disagreements → personal accusations

Voters were asked to judge the candidate’s character, not their ideas.

A shift from information → fear

Speculative harms replaced documented policy discussion.

A shift from dialogue → distrust

The flyer encourages readers to treat a neighbor as inherently unsafe.

A shift in emotional climate

Several residents reported confusion, anxiety, and reluctance to participate after this flyer circulated.

These patterns show how one document can reshape the tone of an entire election. While disagreement is expected in any election, it is unusual for HOA materials to focus so extensively on a single neighbor’s character rather than on governance issues.

Is This Targeting a Neighbor?

A quick-check list for evaluating personal or alarming election messages

Ask whether the claims are verifiable. If a flyer lists serious allegations without citing minutes, records, emails, or policies, treat the statements as unverified—not established fact.

Look for emotional triggers. Words that create alarm—danger, chaos, threats, violations—are meant to provoke a reaction. Pause and consider whether the message gives information or just emotion.

Notice when hypotheticals are presented as certainties. Statements framed as “imagine,” “would,” or “could” describe possibilities, not facts.

Distinguish behavior from interpretations of behavior. There is a difference between: “This happened,” and “Someone says this happened.” If the flyer does not show documentation, the claim is an interpretation.

Ask what information is missing. If the flyer names a problem but does not describe the policy, show evidence, provide context, or explain the process, that omission is meaningful.

Check whether the message focuses on people or on policy. Flyer messaging centered on personality instead of bylaws or procedures is using personal framing—not governance framing.

Pause before believing or repeating alarming information. If a message creates alarm, take time to think before accepting it or passing it along.

Closing Thoughts

Ken Lake is strongest when neighbors feel informed, respected, and included.

Analyzing the communication patterns in this flyer helps us understand how quickly an election can move from discussing ideas to navigating personal accusations. It also helps us see that deep sincerity does not guarantee accuracy, and that unchecked stress can lead any of us—without realizing it—to speak in ways that make our shared environment less safe.

By paying attention to tone, structure, and verifiable information, we can build a healthier foundation for future elections: one where neighbors disagree without fear, participate without pressure, and trust that campaigns will center policies rather than people.

Comments