Authority and Accusation

- friendsofkenlake

- Dec 10, 2025

- 6 min read

Updated: Jan 9

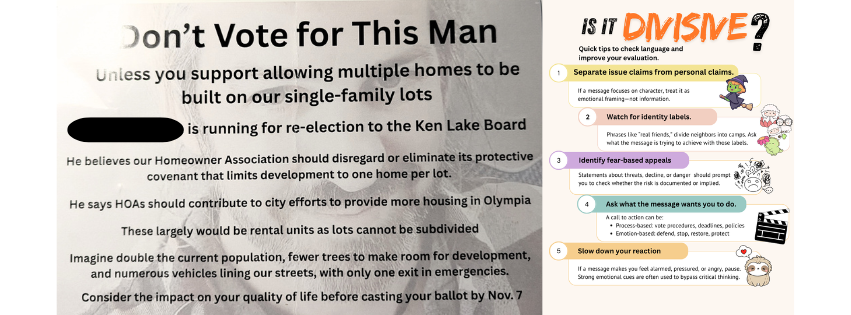

A communication analysis of a candidate letter circulated during the 2025 Ken Lake election

The two-page letter signed by Board President Mike Gowrylow was one of the most aggressive campaign documents distributed during the 2025 Ken Lake election season.

Unlike typical HOA communication or even standard political comparison, the letter focused almost entirely on character attacks toward one neighbor, naming him repeatedly across two pages and framing him as manipulative, dangerous, and personally responsible for a long list of perceived harms.

I was doorbelling when a neighbor handed me this letter. I actually laughed out loud — not because it was funny, but because the bias was so open and the authority so assumed. Nothing in the letter tried to justify its claims beyond “trust me, I’m the president.” — Elle

This analysis looks at how the letter communicates — its tone, structure, emotional hooks, and rhetorical choices — and how those choices shaped the election environment. It is based solely on the exact text delivered to each home, which we will post in our next article.

A Tone of Indictment, Not Dialogue

From its first lines, the letter adopts a tone of moral condemnation. Instead of explaining policy disagreements or offering alternative solutions, it frames the targeted candidate as a kind of community threat. Accusations are presented as settled fact, including claims of “egregious behavior,” “splitting the community,” “demeaning board members,” “threatening candidates,” and “wild, non-attorney interpretations.”

The voice shifts repeatedly between indignation, mockery (“Really?”), and moral outrage (“This is pure B.S.”). At times the letter reads less like HOA communication and more like a political broadside — not written to inform, but to isolate.

The emotional posture is clear: You should be alarmed, and I am telling you who to blame.

A Case Built Through Stacking Accusations

The structure of the letter mimics a prosecutorial brief: name the villain, establish a pattern of misconduct, list allegation after allegation, then conclude by urging the reader to vote against him.

Throughout both pages, accusation builds upon accusation. More than two dozen distinct claims appear, none accompanied by minutes, dates, quotes, emails, or evidence. The letter relies on volume rather than verification — a strategy commonly known as accusation stacking, where the quantity of claims substitutes for proof.

This is one of the most recognizable formats in political propaganda: use repetition to create the feeling of a pattern, even when no documentation is offered.

By the time a reader finishes the letter, the emotional effect is clear. The author does not need evidence; he has created a story in which evidence feels unnecessary.

Fear as the Emotional Engine

While the accusations occupy much of the space, the emotional weight of the letter comes from fear. Large portions of the text ask the reader to imagine catastrophic outcomes:

streets overflowing with cars,

parks “crowded” and unsafe,

the “single-family nature” of the community collapsing,

covenants becoming unenforceable,

gates removed,

“hungry homeless individuals” bathing in the lake,

and even the possibility of “campsites” in the forest.

These scenarios are presented not as possibilities but as looming consequences tied to one candidate.

Speculated future decline becomes a substitute for evidence of present wrongdoing.

This is how fear-based messaging works: You feel threatened, so you accept the story of who the threat must be.

Delegitimizing the Target

Beyond fear, the letter engages in systematic delegitimization. The targeted neighbor is described as untrustworthy, manipulative, dishonest, coercive, unstable, self-serving, and incompetent. His motives are assigned to him, his behavior is interpreted for the reader, and his character is framed as the cause of nearly everything that has gone wrong.

This rhetorical pattern — stripping a person of agency, competence, and good faith — is called depersonalization in conflict communication. It presents disagreement not as a difference in approach but as evidence of personal defect. In extreme forms, depersonalization creates a social permission structure for exclusion: “Someone like this should not be part of our community decision-making.”

The letter leans heavily into that frame.

Borrowing Authority Without Offering Evidence

Throughout the text, the writer repeatedly positions himself as the only reliable narrator.

The phrase “I currently am president of the board” appears prominently at the beginning, functioning almost like a credentialing stamp. The authority of the office is used as implicit proof — even while no actual evidence is presented.

This technique is known as authority borrowing: implying institutional legitimacy even when offering personal opinion. Readers may feel that they are receiving insider knowledge, when in fact they are receiving one person’s interpretation.

Internal Contradictions Reveal the Strategy

Several contradictions appear directly within the letter itself — not from outside fact-checking, but in the letter’s own logic.

The letter condemns fearmongering while engaging extensively in fearmongering. It denounces character assassination while delivering two pages of it. It claims the opposing website uses “propaganda,” then uses propaganda techniques itself. It accuses the candidate of “charging without evidence” while offering no evidence. It warns of “division” while writing a document guaranteed to divide.

These contradictions are not accidental. They reveal the letter’s core strategy: Control the narrative by accusing the target first — and of everything.

This is a conflict pattern known as preemptive framing. Once framed, anything the targeted person says in response appears defensive or self-serving, because the emotional story is already set.

Recognizable Propaganda and Conflict Techniques

Even without bullet points, we can name the techniques clearly:

Accusation stacking – overwhelming the reader with claims so no single one can be examined in depth. AKA: The Gish Gallup

Fear projection – presenting hypothetical disasters as near-certainties.

Authority borrowing – implying official verification where none exists.

Straw-man framing – attributing extreme positions (“open the parks to homeless people”) not supported by documentation.

Loaded language – using emotional phrasing to provoke judgment.

Moral panic imagery – invoking decline, chaos, or threat to identity.

Depersonalization – framing a neighbor as fundamentally dangerous or unstable.

These are textbook persuasive techniques — highly effective emotionally, but corrosive to civic discourse.

The Overall Impact on the Election Climate

The letter shifted the election conversation from shared governance to personal alarm. Instead of comparing candidates’ skills, experience, or ideas, it asked neighbors to respond to a threat narrative — and provided a villain to attach that fear to.

Messages like this don’t merely influence votes. They shape the emotional climate in which neighbors talk to each other, evaluate information, and decide whether it feels safe to participate.

When a letter like this becomes part of the election environment, the result is predictable:

Facts become harder to distinguish from interpretations.

Neighbors feel pressured to pick sides.

New voices grow quieter.

Conversations become tense rather than curious.

Fear replaces trust as the basis for political choice.

That is why analyzing tone matters. Messaging is not just words — it is the scaffolding for how a community understands itself and one another.

Now that we have discussed the framing of the letter, we will spend another article going over the claims in more detail. This is our neighborhood, after all, and we all need to ask…what if he is right?

Using What We Know Sometimes, when I am unsure of how to weigh information, I look at outcomes for each side of the decision: what if I'm right, and what if I'm wrong? What happens? Who is hurt? What is the benefit? If Mike is right… If every accusation in the letter were true — if one neighbor really were manipulative, coercive, disruptive, or unethical — then we have to ask: Does this letter model the kind of leadership we want in response? Because even if the content were accurate, the communication style was:

If the concerns were legitimate, the response should have been:

Not a two-page community-wide denunciation. In other words:

If he’s right, then the method still fails the standards of fair governance. Accuracy does not justify escalation. Truth does not require character destruction.

If Mike is wrong… If the claims are exaggerated, misinterpreted, or unsupported — as the documents strongly suggest — then something even more serious has occurred: A neighbor was publicly vilified, isolated, and portrayed as dangerous without evidence. And the consequences don’t stop with one person:

If Mike is wrong, then we did more than misjudge one person. We participated — knowingly or not — in excluding a neighbor from their own community. The Core PointRegardless of which scenario you believe, the conclusion is the same: This letter is not a model for healthy leadership. And it is our responsibility to prevent harm either by choosing to not believe the accusations or by asking questions and doing the work to find solid ground. |

Comments